Home

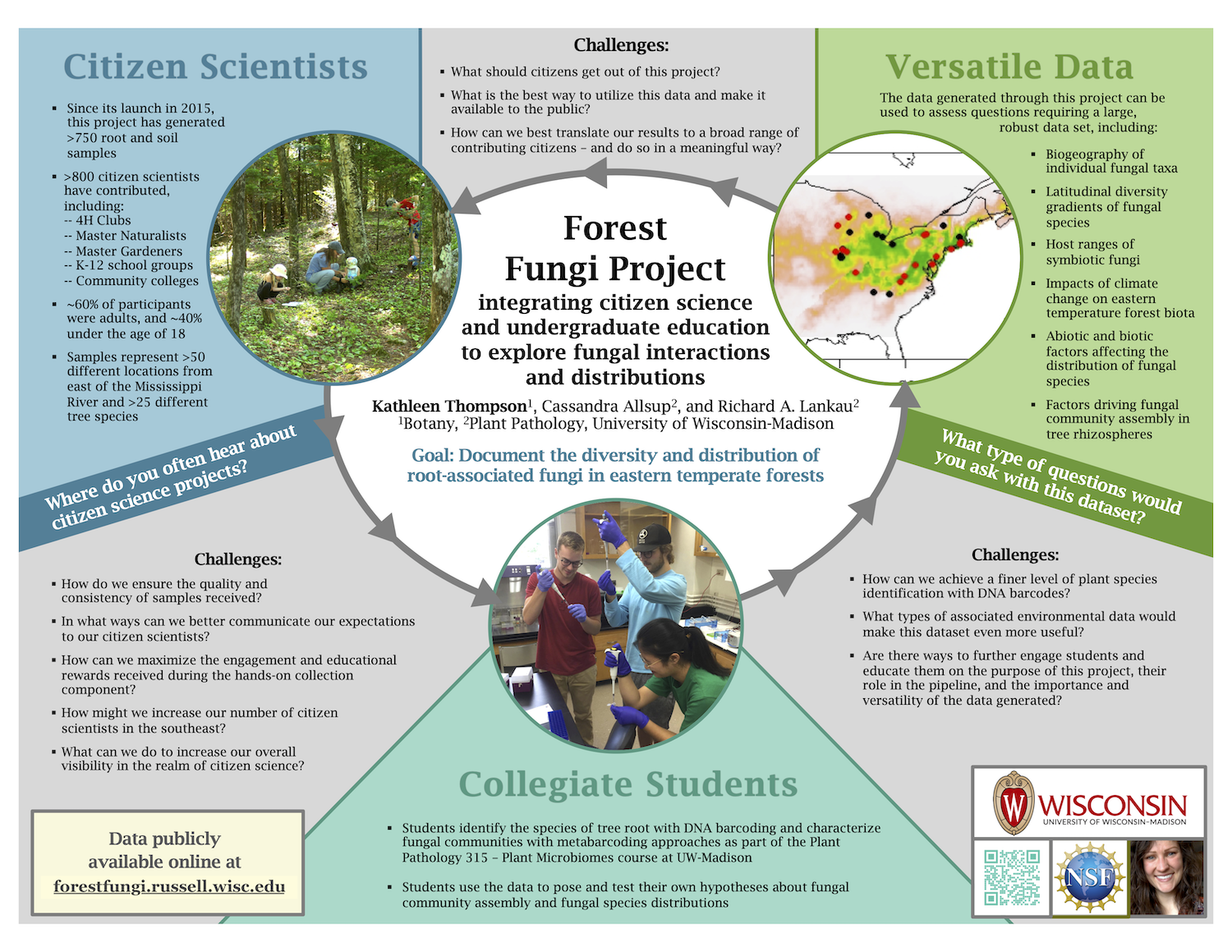

The Forest Fungi Project is a community science project that was launched in 2015 by the Lankau Lab of the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Our aim is to engage the broader community in the process of scientific research while generating data to address important ecological questions.

Participation is easy – and fun! We invite, and encourage, you to get involved today. Click ABOUT in the upper menu to learn more about the project, and click PARTICIPATE to find more information on how to get started.

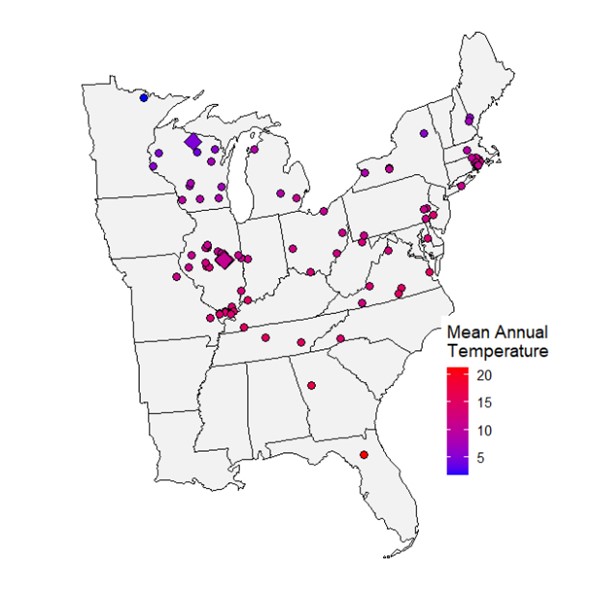

Volunteer root sample locations 2015-2025

See sampling sites on Google Earth https://earth.google.com/earth/d/13Qm42Tr6TQD_1lef4tEysQWsaANdaUHR?usp=sharing

Forest Fungi Project News

Ecological Society of America conference Dr. Kathleen Thompson

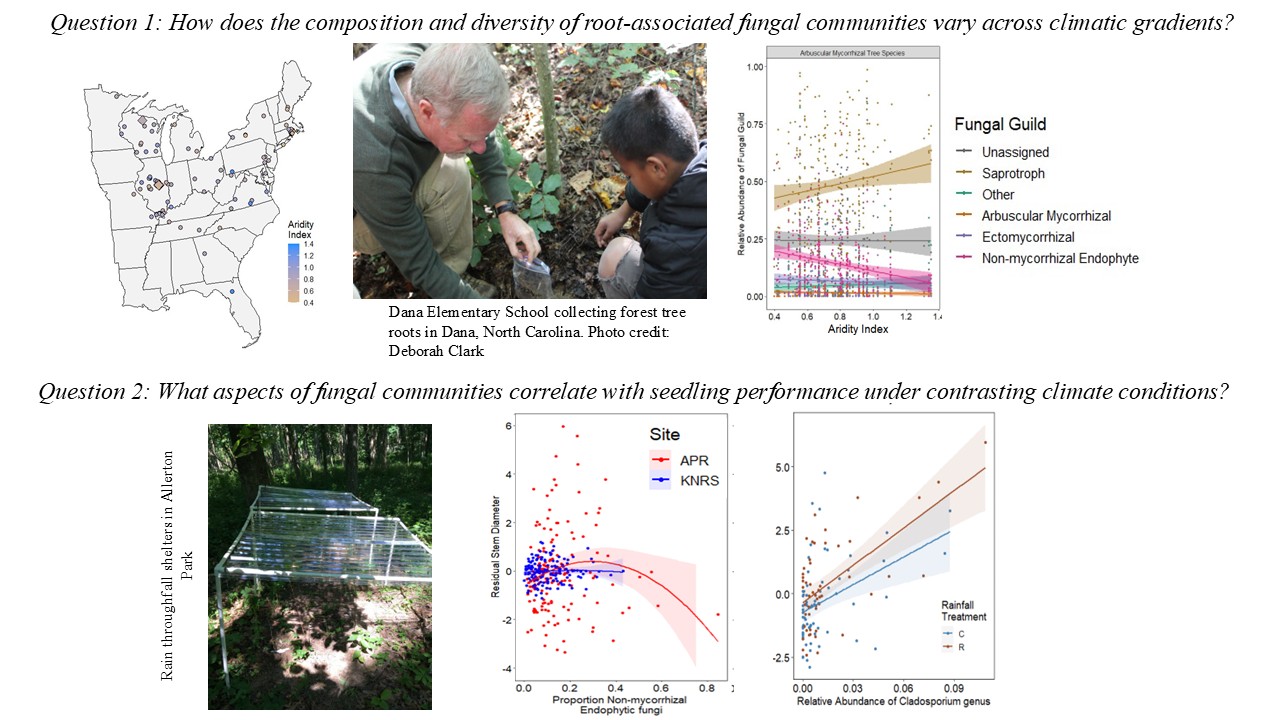

Journal of Ecology Publication Allsup, C., K. Thompson, I. George, R. Li, K. Fontana, S. Fisher, C. Hansen, and R. Lankau. (2025) Tree-fungal interactions across climatic gradients: What is the potential for tree niche expansion via varying fungal associations? Journal of Ecology DOI: 10.1111/1365-2745.70109

Changes in precipitation and temperature are causing tree species and forest types to shift their current distributions or tolerate current distributions. Forest trees have specific climatic conditions (such as temperature and precipitation) that are required for survival. Trees have different strategies to tolerate changing climates. For example, in drought conditions, forest trees may be able to grow deeper roots, evolve to have deeper roots, or associate with soil microbial communities that enhance tolerance in dry conditions.

More than half of earth’s species live in soil, as microbes. Soil biotic communities include archaea, bacteria, fungi, nematodes, earthworms, and vertebrates, all of which can impact a tree’s ability to tolerate stress or changing climates. For example, our lab favorite, mycorrhizal fungi, provides a host of benefits, including enhanced nutrient and water uptake and disease resistance. If unique soil microbes provide tolerance to trees and are available in soils, will trees be able to expand into new areas and/or stay in the current areas?

Before this question could be answered, it was important to document tree root fungal communities across climates and species. Between 2015-2022, we partnered with 1,000 Forest Fungi Project scientists and received 950 tree root samples from 20 states. This included over 20 different tree species from all over the United States. Our main contributing scientists were 4-H groups, home schools, public schools, and volunteer programs, such as Master Naturalists. (Shout out to Illinois Master Naturalists!!). The broad geographic sampling of tree roots would not have been possible without the contributions from Forest Fungi Project Scientists. In “Tree-fungal interactions across climatic gradients: what is the potential for tree niche expansion via varying fungal associations?”, we incorporated data from Forest Fungi Project scientists and experimental data. These data showed that fungal communities were indeed impacted by climatic conditions. Interestingly non-mycorrhizal endophytes (not well studied) increased in hotter drier conditions. One species of non-mycorrhizal endophytes, Cladosporium, emerged as a candidate root fungal that could allow Acer trees to tolerate climatic conditions outside their normal range.